|

|

|

|

|

|

All resistants, who play a role in this story on Valkenburg and its surroundings.

– 55 persons

Berckel Karel Clemens van, Heerlen

Berix Jan Willem , Heerlen

Betuw Johannes Petrus Maria van, Heerlen

Brands Lambert , Valkenburg

Caldenborg A. , Houthem

Caubo Jean-Michel , Schin op Geul, Paris

Cobbenhaegen Frans Alexander ,

Coenen Jan Hubert , Simpelveld

Corbey George , Valkenburg

Cornips Constant Jozef Ernest , Heerlen

Crasborn Jacobus Reinier Peter , Heerlen

Cremers Anna Maria Johanna , Voerendaal

Cremers Hein , Valkenburg

Cremers Wielke , Valkenburg

Dahmen Leo , Valkenburg

Delahaye Pauline ,

Donners Kaspar , Valkenburg

Flachs Käthe ,

Francotte Wilhelm Joseph , Vaals

Freysen /Freijsen Wilhelmus Agathus Petrus , Valkenburg

Geelen Theodorus Gertrudis Hubertus , Meerssen

Goossen Theodorus Johannes Maria , Kerkrade

Gronden Abraham Cornelis van der,

Gronden Gerrit Jan van der, Valkenburg

Grotaers Coen , Berg en Terblijt

Hendriks J. , Berg en Terblijt

Hennekens G. Hub , Valkenburg

Horsmans Gerardus Aloysius Antonius ,

Horsmans Willem Bernard Jozef ,

Hout Johannes Franciscus van, Tilburg

Jansen Sjir / Gerard , Geulhem

Jaspers Marie-Thérèse , Klimmen

Kooten Bartholomeus Johannes Cornelis van, Klimmen

Laar H.J.R. van, Margraten

Laeven Albert Hubert ,

Laeven H.P.August , Schin op Geul

Lambriks Jo , Valkenburg

Meijs Sjeng , Valkenburg

Nijst Charles Joseph , Valkenburg

Ogtrop Harie van, Valkenburg

Peusens gezusters ,

Prompers Nicolaas Maria Hubertus , Heerlen, Broekhem

Roks /Rocks Jan Joseph , Valkenburg

Roy Hubertus Andreas van, Valkenburg

Schoenmakers F. , Sibbe

Schunck Peter Joseph Arnold , Valkenburg

Schunck-Cremers Gerda , Valkenburg

Smits Gerard Frank , Hulsberg

Soesman Gerhard Lodewijk Robertus , Maastricht

Starmans J. , Valkenburg

Ven Johannes Hendrikus op de, Valkenburg

Vroemen Joseph Hendrik Hubert , Valkenburg

Westerhoven Jan van,

Willems Victor Benedictus Josephus , Valkenburg

Wolf G.A. , Sibbe

Our soldiers can no longer do anything. Now it is our turn.

We will get in the way of the Germans wherever we can.

Henri Vullinghs on the first day of the occupation, May 10, 1940.

Resistance in Valkenburg

during World War II.

Memories of Pierre Schunck and other original textes, collected and commented by Arnold Schunck

This website is under a Creative Commons license:

This website is under a Creative Commons license:

• No commercial use

• No changing

You are free to share — to copy, distribute and transmit the site, also partially, but not for commercial purposes..

You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work and of course you have to indicate the author and the source as well as the license conditions.

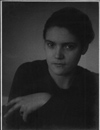

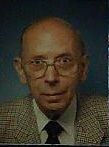

Pierre Schunck, ∗ 24-03-1906 in Heerlen, ⚭ 03-10-1936 Gerda Cremers in Valkenburg, † 02-02-1993 in Kerkrade.

He gained fame mainly because he led the resistance organization L.O. in Valkenburg during WW2.

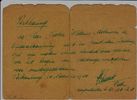

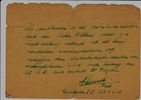

Identity Cards of the Resistance for Gerda and Pierre Schunck-Cremers

Issued by „Voormalig Verzet Limburg“ (Association of Veterans of the Resistance), registration number (KvK) V 187800

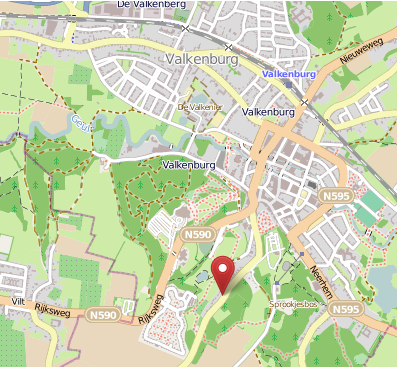

One of the regular occasions on which the members of the VVL met was the annual commemoration in September of their fallen comrades on the Cauberg in Valkenburg. Because in September 1944 most of Limburg (NL) was liberated. In the meantime, this reunion does not take place anymore, as the former resistance fighters are either already deceased or too old. The commemoration of the dead on the Cauberg now takes place, as everywhere in the Netherlands, on May 4.

- Introduction

- Before World War II

- Unorganised Resistance

- Organised Resistance

- Redistribution Clothing for “divers”

- Founding of the L.O. district Z18 (Heerlen)

- The “diver’s inn” in the Caves of Meerssenerbroek

- Building up the “diver’s inn”

- Coen Grotaers

- One unit in every village

- Turkish passports

- District Leader Berix

- The L.O. district of Heerlen 2

- Meetings

- Female couriers are surer

- The stream of the divers increases

- The verger in the confessional

- The Jews in Valkenburg

- Traitor

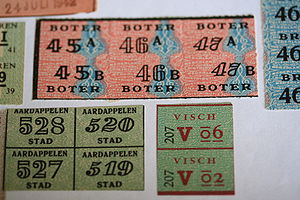

- Manipulations with Food and Cards

- The Raid on the Distribution Office in Valkenburg

- The Raid on the Distribution Office in Heerlen

- Butter and Eggs

- St. Joseph Hospital

- End of the “diver’s inn” 1

- An Own Intelligence Group

- The disappearing of the residents’ register

- Two Resistance Men shot on the Cauberg

- The End of the War and afterwards

- The Liberators are Approaching!

- The Liberation of Valkenburg

- What did the organisations L.O, K.P., O.D. and R.V.V.?

- The murder of the Nazi collaborator

- Evacuation

- Food for the caves

- Kerkrade destroyed, the entire population fleeing. A large part of the refugees in Valkenburg

- Allied Killed In Action

- South Limburg is free and now the rest!

- Old Soldiers Never Die. The veterans return

- Veterans (NL) and their fallen comrads

- Death of an Ancient Resistance Man

- Commemorations after the war. What is memory culture good for?

- Epilogue of Cammaert

- Sources and the colors of the margin lines at the left side of the page

- Links WW2 & Resistance

This text is a mosaic of different sources, which I have on this item. It is a patchwork of quotations, because they tell different parts of this story, sometimes the same event, but then they are complementary. Here and there they are connected by a commentary of my own. Much has been adopted literally from interviews. Scans of texts written by Pierre Schunck himself after the war have an important place. Whole pages from his memories look like typewriter font. Because that was it. The corresponding scans can be found right next to it, as a miniature. Click for an enlargement.

Also I wrote, what we, his children, can still remember from his stories.

By the color of the margin line at the left you see at a glance whose words these are. If you move with your mouse over a paragraph, the source is displayed as a “tool tip” text. (Does not work on mobile devices.) Literal quote blocks from the interviews have got a darker background (not in the printed version) and are indented.

Below you find an overview of the sources

| Memories Pierre Schunck | |

| Interview Nederlands Auschwitz Comité | |

| Interview NIOD | |

| History of Valkenburg | |

| The hidden front, doctoral thesis by Fred Cammaert | |

| funeral oration for “Paul”, by Theo “Harry” Goossen |

For more information about these colours, go to Sources.

- External links to websites about World War II and the Resistance in Limburg

- In the text that follows below, you can read the words “district” and “subdistrict”. For practical reasons the Dutch resistance divided the existing provinces into smaller parts. This didn’t correspond to any official classification, but it was only based on the resistance work. They used the words “district” and “subdistrict”. The subdistrict of Valkenburg, whose leader was my father, included Valkenburg itself and some villages. In the beginning it was independent, later it belonged to the district of Heerlen.

- You also will find several times the expressions "hiding people" or "divers". The latter one is the translation of the Dutch word "onderduikers". During the war it was used for all persons, who were wanted by the Germans and for whom it was better to hide, to dive into the underground. It is for them that the organization L.O. was founded. For Jews, allied pilots who had crashed on Holland, young men who didn’t want to to go to work in Germany in order to replace the German soldiers.

- To protect themselves and others, they used aliases that had the same initials as the real name. For it was still common practice that the initials of a person were embroidered in their clothes. A famous example is the organizer of the French Resistance Jean Moulin. Amongst others, he had the pseudonyms Joseph Mercier and Jacques Martel. The resistance people knew of each other only these pseudonyms. The real names became known only after the war, but on commemorations and other meetings they usually still used the resistance names. Pierre Schunck called himself Paul Simons.

Introduction

What is a commemorative culture good for?

When preparing the commemoration celebrations Valkenburg 2019 – 75 years liberated, it turned out that almost nobody knew what the resistance in Valkenburg did. In fact, it was hardly known, especially among the youth, that there had been a resistance against the Nazi’s at all. Why is it important that this memory is kept alive? Of course, many will immediately answer, because that should never happen again. Of course that’s true, but everyone knows that history is NOT repeating itself. Hitler is dead and the current right wing populists are not just a copy of the Nazi’s. But still, there have been things back then that we still have to watch over now.

The Gestapo (Secret State Police) would have been jealous of all the options available to today’s internet giants, such as Google, Amazon, Facebook and so on, to spy on us. Today this is not done for political but for commercial reasons. The fact that the religion of people is registered in many countries does not have any political reason either. But still: when the Nazis came to power in Germany, they immediately kwew how to find the Jews, the gypsies, the unionists, the communists etc. When the wrong government is in power, all data collected can be used against us. In China this is already happening in a very effective way.

The resistance started small, almost unnoticed even by those who committed resistance. Until they suddenly realized that they were in the middle of it.

With fascism it is just like that. It starts small. Bullying at school or at work. “Because” someone is different. Different belief, different skin color, different gender orientation – whatever. And in order not to be completely shut out, the victim often laughs with them. Bullies therefore often do not even notice that they are bullying someone. It becomes worse when that bullying happens in order to make feel better the bullies as a group. This way especially disadvantaged groups often feel attracted by foreigners’ haters. Because “we don’t have nothing, but at least we are civilized people“.

Then suddenly it becomes a movement, a party, a mass murder.

If you see someone inciting to hate others, say NO. If you see someone being excluded because he or she is different: resist!

Because the resistance that’s US!

Valkenburg, an important center for people in hiding

This text is from my contribution to the memorial book “Valkenburg 75 years liberated”

The organized resistance in Valkenburg consisted mainly of assistance to hundreds of people in hiding, the so-called onderduikers, which is the Dutch word for divers. For example, men who did not want to work in the German war industry. The subdistrict consisted of Valkenburg, Berg and Terblijt, Sibbe, Margraten, Schin op Geul, Klimmen and Houthem. Each parish had a diver’s leader who had direct contact with the diving addresses. Couriers (mostly women) maintained the connection with the district management. Less and less was written down because of the dangers. Partly because of that, but also because of stupid luck, the LO had no losses in Valkenburg.

Since 1943, people who wanted to go into hiding came in increasing numbers from all parts of the Netherlands, although there were many German soldiers in the seized hotels in Valkenburg. But the presence of so many occupiers turned out to be a plus. Except for the KP-people Coenen and Francotte, who were beaten from one hotel to the other, before they were murdered on the Cauberg during the last days of the occupation. (The KP was the armed arm of the resistance in South-Limburg. They had their HQ in a farm in Ulestraten.)

Quite a lot of people in hiding worked in hotel kitchens, etc. They could therefore earn their own livelihood, as well as people in hiding who were housed with farmers. They hardly needed help in the form of coupons. Many of those, who were in hiding with farmers, received an agricultural exemption from Brands, the boss of the food local agency and could then legally reside and work there.

The rest of about one hundred and fifty people in hiding needed help from by means of ration stamps. That number fluctuated. There are no precise numbers, since they did not write down anything. At the distribution office next to the current chairlift to the Wilhelmina tower, the officials Freysen and Willems put aside between five hundred and eight hundred ration cards every month.

…

The Jews of Valkenburg did not survive the war to a large extent. Almost nobody could believe that those stories about extermination camps were real. But dozens of Jews, also from elsewhere, found shelter here.

Arnold Schunck, son of the subdistrict leader Pierre Schunck

I have to add: I do not know anything about the fate of Sinti or other Roma in Valkenburg, if here were any at all during the occupation.

The resistance against the German occupation during the second world war began on the first day. Spontaneously, disorganized. As forms of civil disobedience. Gradually, particularly the aid to “divers” was organized (This was how people were called, who had to hide from the Nazis for various reasons). It was not a major military contribution to the victory of the allies. The hiding of young men who had to go to Germany to do forced work certainly harmed the German war industry anyhow. But in particular, many lives were saved. Here you find the story of Pierre Schunck and his people, which was typical of this resistance.

However, in some respects the resistance in the province of Limburg and in Valkenburg differs from the rest of the country. The main points:

- In Valkenburg we have to consider the particularly high proportion of supporters of the national socialist party N.S.B. (1935 in Valkenburg: 23.4 %, national average: 7.94%, Limburg altogether 11.7 %, mining district of Limburg 17%). That made resistance especially dangerous in this community.

- Long before the arrival of the German troops, the Dutch archbishop declared the membership of Nazi organizations incompatible with Christianity. Other churches made similar statements . In those years, the dutch province of Limburg was still very Catholic, which meant that large sections of the Catholic clergy quickly took a leading role in the resistance. In the Limburg mining area, the cooperation with trade unionists , socialists and communists was smooth despite ideological differences.

- Limburg was, like the other border provinces, an important area for taking in people from the densely populated West of the country, who had to go into hiding. In the tourist town of Valkenburg, they were housed not only in farms, but also in hotels . See also the epilogue of Cammaert at the penultimate page.

- The geographical position at the southeast corner of the Netherlands, made this region suitable as a transit area for many refugees and allied pilots to Switzerland or Gibraltar. That was an important activity especially in the many border towns . For Valkenburg itself this played a minor role.

This text is a mosaic of different sources, which I have on this item, here and there with a connecting commentary of my own. On the color of the margin line at the left you see at a glance where they come from. If you move with your mouse over a paragraph, the source is displayed as “tool tip” text. Literal quote blocks from the interviews have a darker background (not in the printed version) and are indented.

Below you find an overview of the consulted sources

Before World War II

Pierre Schunck (*24-03-1906, Heerlen †02-02-1993, Kerkrade) was the eldest son of the Dutch businessman Peter J. Schunck and Christine Cloot.

Settela Steinbach,

May 19th, 1944

Already as a student, Pierre Schunck showed a social feeling. Or was it also his desire after an interesting life, that made him help in the Sinti (gypsy) camp near the Heksenberg in Heerlen with a program to teach the children? My father made this job for the Steinbach family. This pleased the mother so much that she promised one of her daughters to him. This, however, never became true.

There were successively several women, who were called ”Mutter Steinbach”. In this case this was probably the later ”old” mother Steinbach, Johanna Bamberger (1893-1935).

The camp was opened on October 27th, 1923. Pierre Schunck was then 17 years old. The Franciscan Justus Merks of the ”Woonwagenliefdewerk” (Caravan work of love) was pastor there and the driving force behind things like the literacy of the children. Perhaps Pierre was inspired by him to become a Franciscan.

As was to be expected, the Nazis killed most of the Sinti people in Limburg, including the Steinbach family.

The genocide of the Romani in Limburg and elsewhere

Who does not know the image of Settela Steinbach looking during the war out of the cattle wagon, with which she is going to be transported to Auschwitz? She was born near Sittard, she belonged to this same family Steinbach. Only her father survived the war and died in 1946 in Maastricht.

Johanna Bamberger (1893-1935) was called the “old mother Steinbach”. She was mother, later grandmother and great-grandmother of the family, where Pierre Schunck gave tutoring in the twenties.

About the Sinti people around the Heksenberg a richly illustrated book was published, which now has its second edition: Settela en Willy en het geheim van de Heksenberg (Settela and Willy and the mystery of the witches’ mountain), ISBN 978-90-822416-3-1, available at the Thermen Museum, Coriovallumstraat 9, Heerlen or at http://www.landvanherle.nl/bestellen

Apart from the beginning, the following movies about the book on YouTube come almost completely without text:

Video 1

Video 2

This picture comes from the second video.

Corresponding to the tradition ruling in that time, the family early made clear to Pierre: “Your future lies here in the business, except if you want to become a priest.”

For different reasons Pierre felt more attracted to become a priest. He completed his studies in Megen near Nijmegen and Hoogcrutz (at the southern edge of southern Limburg). But he left the monastery again before the ordination to priest.

After the time in the monastery in the thirties, he managed by order of his father’s company a laundry in Valkenburg. For lunch he often went to hotel Cremers, which was owned by the parents of a friend, Joop Cremers. There he met his latter wife, Gerda Cremers (DB).

World War II has exerted a big influence on their further life. Due to their moral and national convictions, Pierre and Gerda saw only one possibility: to stand up against the German occupation.

The Hollandsche Stoomwasscherij (= steam laundry) was founded in 1904 on the Plenkertstraat in Houthem (later Valkenburg) by Pierre Cloot from Heerlen, father of Christine Cloot and father in law of Peter J. Schunck. Christine and Peter married in the same year. Peter became owner in 1909, while Leo Cloot became the director. In this case, the Rijckheyt Archive confuses Pierre Schunck (who was 3 years old at that time) with his father Peter Schunck.

Pierre became director (not owner) in the thirties. The laundry was sold in 1947 to E. Hennekens.

See also the inventory list of the archives of Leo (L.H.M.) Schunck in the above-mentioned Rijckheyt: A.12 Hollandsche Stoomwasscherij P. Schunck te Valkenburg, 1904 - 1947

Unorganised Resistance

The First People to Hide (May 1940)

How did one get into such a dangerous resistance adventure?

One didn’t decide to join the resistance. Events, sometimes small incidents, made one to step in; the result was that you did something to help other, something that was forbidden by the occupying forces. So you got from one step to the next. I will try to explain it by my own experiences.

May 10th, 1940, on Friday before Pentecost. Warm weather, blue sky. German airplanes in low flight over our house. In Valkenburg, the hostile tanks climb the Cauberg on their way to Maastricht. We are occupied.

Dutch soldiers, who operated an old cannon on the Cauberg before, tipped over the monster in the middle of the street to hinder the Germans in their advance and then disappeared themselves. They are sitting along the slope of the wood in front of our house, the “Polverbos”, and don’t know where to go. I see them. I couldn’t leave the boys in the hands of the enemy, could I?

We invited them in our house and my wife, Gerda, immediately was busy to serve a nutritious breakfast to them. Twelve soldiers then had to be changed into civilians. With some improvisation we made it. The staff had started the daily work in the meantime. Consultation with the men of the staff yielded a couple of garments and the soldiers were modified to a bit bedraggled civilian boys. So we had at once the first people to hide (we called them divers) because transportation back home was only possible for a couple of boys from South Limburg (that is the direct surroundings) .

In the week after Pentecost the journey back home was organized for the vacationists run aground in Valkenburg and our boys traveled with them. Some of them sent back the lent civvies properly.

But now to the weapons and uniforms they left. Johan de W., our engineer, knew a solution. He burned the uniforms in the steam-boiler in a nice fire. But, Johan said, we could possibly need the guns urgently to chase the Jerries away. He knew what he did. He removed one part. The weapons themselves were greased thickly, wrapped up with rags and buried in the garden one by one. The parts which he had held separately were greased too, packed and hidden separately into a little box. He proceeded this way so that if the NSB-people or the Germans would find the guns, they would not be able do anything with them.

The rest of this page: Chalices And Mass Gowns

Public Resistance

From: The History of Valkenburg-Houthem:

Many Dutch people went out with a white carnation in the buttonhole on June 29th, 1940, prince Bernhard’s birthday. Because this was the coat of arms flower of the prince. It was the first public resistance act against the Nazi power.

Probably the Dutch people never understood better the words in the national anthem

"de tyrannie verdrijven

die mij mijn hert doorwondt"

(banish the tyranny, that wounds my heart)

than in these bitter years of occupation. The number of resistance fighters grew gradually as a result of the obstinacy with which the Nazi ideology was imposed, the increasing lack of rights, the persecution of the Jews, the shootings of hostages, the numerous deportations to the concentration camps, the forced labor service in the German armament industry, the statement of loyalty, that every student had to sign, as well as the captivity of the Dutch army.

These and many other things nursed the resistance will. The hate for German and Dutch Nazis increased. Public resistance to the merciless oppression and the violation of fundamental human rights happened still more frequently.

Initially this resistance consisted mainly of civil disobedience, but gradually they began also to sabotage. The help to divers followed this pattern too: What started as spontaneous, individual help, became progressively organised at ever higher levels. There was a need of humanitarian help in the first place, but this work also had a military significance: young men who didn’t want to go for forced work to Germany, to replace the soldiers in the (armament) industries and food production there, were hidden. Crashed allied pilots were “dispatched” to Gibraltar via the so called pilot line. The story of Pierre Schunck is very typical. He has never “planned” it. You could almost say: it occurred to him.

There were other examples of civil disobedience, in which most people joined in. For instance, everyone who had the opportunity to do so, kept a few chickens, a goat or a pig to have something beyond the rations. These animals had to be registered with the distribution office, and then one got less rations. To circumvent this, they often registered less animals than they really had. Family Schunck also had a gaggle of chickens behind the laundry, of which only a few were registered. If an inspector would come to check the number of the animals, a signal would go backwards, and the chickens would be chased by someone of the staff in the adjacent orchard. This was a popular sport, which already bore the seeds of rebellion inside.

Chalices And Mass Gowns

For one year nothing happened. The Germans softened on nice, our soldiers, who were prisoners of war, were allowed to go home again and we wondered: “Why did we expose ourselves so much to danger by helping these boys? They are officially and properly at home now.” Until the rumor startled Valkenburg that the SS had expelled the Jesuits back to Germany and confiscated their cloister. The rumor was largely true but not all of the fathers returned to their native country. The superior and a couple of further fathers went underground at rector Eck, an uncle of my wife and pastor of the Franciscan nuns cloister St. Joseph in Valkenburg-St. Pieter.

The Antique Books

After the liberation, Pierre Schunck looks at the antique books that were saved from the Jesuit Monastery in Valkenburg in October 1942.

Photo: Dwight W. Miller

Source: https://nimh-beeldbank.defensie.nl/beeldbank/

Film

In October 1942 the evacuation of the Jesuit monastery took place in Valkenburg, in which there was a unique collection of books and a planetarium. A high S.S. delegation went to Valkenburg specially for this purpose. Within a few weeks the monastery church was demolished to the last stone.

…

The monks had literally been put on the road. Since then the building was at the disposal of the Hitler Youth. Should be: Imperial school of the SS

Read also the wikipedia article in German about this Reichsschule der SS or in Dutch

At http://nederland-in-oorlog-in-fotos.clubs.nl/foto/detail/10963416_1942-valkenburg-reichschule01 we read about that theological college: The Jesuit monastery was built in 1893-1895 according to plans of H.J. Hürth as Collegium Maximum or Ignatius College for German Jesuits. A wing and a library were added in 1911. In 1943 the chapel was demolished and from 1948 to 1961 the building was empty. Then it was involved by the Franciscan Sisters of St.Joseph.. These sisters were already in Valkenburg, on Sint Pieter at that time. This monastery with German religious was also created during the "Kulturkampf" under Bismarck.

At that time, W. Eck was rector there. He came from the Dutch side of the German-Dutch border, had a German father and was therefore suitable as a chaplain for German nuns.

We continue reading the original text of Pierre Schunck: „But not all of the monks…

were gone back to their native country. The superior and some other fathers went hiding at the rector of St.Pieter’s monastery, Rector Eck, an uncle of my wife.

He called me with the urgent request to visit him. I only thought that the sisters of St. Pieter were now to be evacuated to Germany. They too were of German origin. But the German monks were sitting in the rector’s room. They had only one big concern. Namely the sacred vessels and precious robes, to which they attach a sacred value, should not fall into the hands of the pagan SS.

Their expulsion from the monastery was already a few days old, and several families in Valkenburg (especially Caselli and Wijsbek-Caselli) had already secured paintings and other accessible things. They had been able to do so easily because the monastery had been abandoned for some days. But now a construction firm was there with workers, to prepare the imminent arrival of the Reichsschule. The monks asked me, as a president of K.A., whether I knew someone who would dare to bring out their precious possessions of monstrances, chalices, mass gowns and relics. They were in a safe under the sacristy of their church. I promised to see what could be done and they gave me the keys of the monastery and sacristy.

Pure coincidence collaborated again. A construction supervisor of the work in the monastery called, whether we could not pick up, wash and return the dirty laundry left by the Jesuits. This was the great opportunity to execute the “chalice job” on the bright day. The vans were all on the road, but the horse and the waggon were at home. My neighbor, Kaspar Donners, and me myself, went there, equiped with some laundry baskets. After we had the baskets almost full, I also went to the sacristy to see if there were not “dirty liturgical vestments” too. We put the monstrances, chalices, and liturgical vestments under the dirty clothes, and the workers helped us to hoist the heavy baskets on the waggon and Kaspar and I came home unharmed. Uncle Eck could calm the fathers, that everything had gone according to their wishes. We however were saddled with a great value of “enemy fortune”. But that was not yet all.

The Reichsjugendführer Rosenberg came from Lithuania. The new board (of the Reichsschule) wanted to give him a precious book collection from Lithuania and there was something like that in the library of the Jesuits. But they could not find anything, because the index card box was mixed up. So the Father Librarian was brought back from Germany. He had to assemble these books. Well, this priest asked me to continue to wash the laundry of the Reichsschule. He said to be able to hide some books under the clothes when the driver would come.

He also smuggled out small books himself, hidden under his long robe. And so every week, as long as the Father worked there, a precious book came to us. In the wardrobe in our bedroom hung precious hand-embroidered chasubles, behind our clothes the chalices were hidden. And in the archive room behind the office stood the old books. It soon ruggedly became clear to me that this storage method was life-threatening.

Potatoes and Weapons

Spring 1942

With the ladies of the “Catholic Action” and farmers from the surroundings, Paul and his people also manage to set up a kitchen for children as an alternative to the (Nazi-) Winter Help. They got hold of the kitchen equipment in the Reichsschule and set it up in the attic of Paul’s laundry:

were gone back to their native country. The superior and some other fathers went hiding at the rector of St.Pieter’s monastery, Rector Eck, an uncle of my wife.

He called me with the urgent request to visit him. I only thought that the sisters of St. Pieter were now to be evacuated to Germany. They too were of German origin. But the German monks were sitting in the rector’s room. They had only one big concern. Namely the sacred vessels and precious robes, to which they attach a sacred value, should not fall into the hands of the pagan SS.

Their expulsion from the monastery was already a few days old, and several families in Valkenburg (especially Caselli and Wijsbek-Caselli) had already secured paintings and other accessible things. They had been able to do so easily because the monastery had been abandoned for some days. But now a construction firm was there with workers, to prepare the imminent arrival of the Reichsschule. The monks asked me, as a president of K.A., whether I knew someone who would dare to bring out their precious possessions of monstrances, chalices, mass gowns and relics. They were in a safe under the sacristy of their church. I promised to see what could be done and they gave me the keys of the monastery and sacristy.

Pure coincidence collaborated again. A construction supervisor of the work in the monastery called, whether we could not pick up, wash and return the dirty laundry left by the Jesuits. This was the great opportunity to execute the “chalice job” on the bright day. The vans were all on the road, but the horse and the waggon were at home. My neighbor, Kaspar Donners, and me myself, went there, equiped with some laundry baskets. After we had the baskets almost full, I also went to the sacristy to see if there were not “dirty liturgical vestments” too. We put the monstrances, chalices, and liturgical vestments under the dirty clothes, and the workers helped us to hoist the heavy baskets on the waggon and Kaspar and I came home unharmed. Uncle Eck could calm the fathers, that everything had gone according to their wishes. We however were saddled with a great value of “enemy fortune”. But that was not yet all.

The Reichsjugendführer Rosenberg came from Lithuania. The new board (of the Reichsschule) wanted to give him a precious book collection from Lithuania and there was something like that in the library of the Jesuits. But they could not find anything, because the index card box was mixed up. So the Father Librarian was brought back from Germany. He had to assemble these books. Well, this priest asked me to continue to wash the laundry of the Reichsschule. He said to be able to hide some books under the clothes when the driver would come.

He also smuggled out small books himself, hidden under his long robe. And so every week, as long as the Father worked there, a precious book came to us. In the wardrobe in our bedroom hung precious hand-embroidered chasubles, behind our clothes the chalices were hidden. And in the archive room behind the office stood the old books. It soon ruggedly became clear to me that this storage method was life-threatening.

in the company had been shut down and the girls stood as nailed on their places. Some cried and sobbed at the top of their voices. The men had gone outside and walked all over in front of the searching policemen whenever it was possible.

Fortunately the gardener, Leo Dahmen, digged in the weapons deeper in another place before and built a potato heap upon them, like they were usual for the winter storage. Another potato heap was at the place which was indicated on the outline. When the policemen began to pull this heap to pieces, loud protest came from the male employees; all of them stood around it there. They said things like: These are our potatoes, hands off, this heap belongs to us, not to the boss, he has nothing to do with it etc. The potato heap was destroyed nevertheless and they found nothing.

“My Son Is No Criminal”

the girls stood as nailed on their places. Some cried and sobbed at the top of their voices. The men had gone outside and walked all over in front of the searching policemen whenever it was possible.

Fortunately the gardener, Leo Dahmen, digged in the weapons deeper in another place before and built a potato heap upon them, like they were usual for the winter storage. Another potato heap was at the place which was indicated on the outline. When the policemen began to pull this heap to pieces, loud protest came from the male employees; all of them stood around it there. They said things like: These are our potatoes, hands off, this heap belongs to us, not to the boss, he has nothing to do with it etc. The potato heap was destroyed nevertheless and they found nothing.

As of this time I was allowed to go inside to my wife. Meanwhile my parents who had come from Heerlen by a cab and chaplain Horsmans sat there, too. Renesse also came in and informed us: „We found copper and about this you will have to answer to the German authorities. So you will be sent to Vught.“ (During the war a German concentration camp was located there.) My wife got order, to prepare pyjamas and toiletries for me. She revolted intensely, she declared that she was pregnant and would go to Vught together with me. I wanted to speak with the chaplain and said: „I would like to confess before I go. “ Renesse permitted this. I asked the chaplain, to contact the engineer Johan because of the weapons, as well as the Jesuits in Maastricht because of her property, so that my wife Gerda wouldn’t further run any risk during my captivity. He promised to regulate everything.

Shortly after this confession Renesse ordered a gendarme to lead me away. I was fastened to his wrist with handcuffs and we had to go by Valkenburg this way. Then my father came into action. He planted himself in front of Renesse and said: „My son is no criminal! Even if he would have hidden weapons, I then would be proud of him. I do not want him to walk tied up onto the street. There stands a cab outside and I insist that you, Mr Offizier, give order to take him away with the cab. If not, then I will inform my son-in-law, who is his brother-in-law, how you humiliate his close relative. And this son-in-law is the local group leader of the NSDAP (German nazi party) in Heerlen.“ Renesse gave way and I went by cab to the police station on the Emmaberg.

The top sergeant sat there. The policeman Renesse wanted to lock me up in a cell, but the top sergeant waved, that I had to come into his office. He sent the young man away and asked me very surprised, what was going on. I answered: „Renesse found copper with me at home.“ By then it was noon. The top sergeant called his wife and asked her to give me something to eat. She brought me a big cup of broth with a beaten egg in it.

Later the top sergeant said after a careful search in different books: „Refer to an ordinance of our Secretary General in The Hague regarding the delivery of copper, alleged to the support of ’Dutch’ Industry. This is a case for the prosecuting attorney’s office, not for the SD in Maastricht!“ ( SD = Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS, secret service of the SS )

Renesse comes in, ignores me and goes to the telephone. The top sergeant, who sits next to it, puts his hand on it and says: „This is a copper case, isn’t it?“ „Yes and I have to inform the SD on it.“

As of this time I was allowed to go inside to my wife. Meanwhile my parents who had come from Heerlen by a cab and chaplain Horsmans sat there, too. Renesse also came in and informed us: “We found copper and about this you will have to answer to the German authorities. So you will be sent to Vught.” (During the war a German concentration camp was located there.) My wife got order, to prepare pyjamas and toiletries for me. She revolted intensely, she declared that she was pregnant and would go to Vught together with me. I wanted to speak with the chaplain and said: “I would like to confess before I go. ” Renesse permitted this. I asked the chaplain, to contact the engineer Johan because of the weapons, as well as the Jesuits in Maastricht because of her property, so that my wife Gerda wouldn’t further run any risk during my captivity. He promised to regulate everything.

Shortly after this confession Renesse ordered a gendarme to lead me away. I was fastened to his wrist with handcuffs and we had to go by Valkenburg this way. Then my father came into action. He planted himself in front of Renesse and said: “My son is no criminal! Even if he would have hidden weapons, I then would be proud of him. I do not want him to walk tied up onto the street. There stands a cab outside and I insist that you, Mr Offizier, give order to take him away with the cab. If not, then I will inform my son-in-law, who is his brother-in-law, how you humiliate his close relative. And this son-in-law is the local group leader of the NSDAP (German nazi party) in Heerlen.” Renesse gave way and I went by cab to the police station on the Emmaberg.

The chief officer sat there. Renesse wanted to lock me up in a cell, but the chief waved, that I had to come into his office. He sent the young man away and asked me very surprised, what was going on. I answered: “Renesse found copper with me at home.” By then it was noon. The chief called his wife and asked her to give me something to eat. She brought a big cup of broth with a beaten egg in it.

Later the chief said after a careful search in different books: “Refer to an ordinance of our Secretary General in The Hague regarding the delivery of copper, alleged to the support of ’Dutch’ Industry. This is a case for the prosecuting attorney’s office, not for the SD in Maastricht!” (SD = Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS, secret service of the SS)

Renesse comes in, ignores me and goes to the telephone. The chief, who sits next to it, puts his hand on it and says: “This is a copper case, isn’t it?” “Yes and I have to inform the SD on it.” The chief warns him that he will get many problems with the public prosecutor heavily if he passes him over. Renesse begins to discuss with the chief why I am not in the cell. “This man is my friend and I don’t close him to a cell.”

Renesse lifted the telephone receiver. I could follow the conversation with the prosecuting attorney’s office in Maastricht (which apparently knew what was happening). They ordered Renesse, to do nothing else but to confiscate the copper and to write a protocol, but no arrest. After that Renesse said to me with a pissed off face: “I have pleaded for you in Maastricht, so this first time we will leave it at confiscation and protocol. As soon as the men come back and report that they didn’t find anything, you will be free to go.” In the evening the men come back and didn’t find anything. Renesse calls my wife with his kindest voice and pretends that he supported it for the judicial authorities to be allowed to let me go.

Crash Course

The chief (DB) warns him that he will get many problems with the public prosecutor if he passes him over. Renesse begins to discuss with the chief why I am not in the cell. “This man is my friend and I don’t close him to a cell.”

Renesse lifted the telephone receiver. I could follow the conversation with the prosecuting attorney’s office in Maastricht (who knew what was happening from the lawyer Joop Cremers, my brother in law). They ordered Renesse, to do nothing else but to confiscate the copper and to write a protocol, but no arrest. After that Renesse said to me with a pissed off face: “I have pleaded for you in Maastricht, so this first time we will leave it at confiscation and protocol. As soon as the men come back and report that they didn’t find anything, you will be free to go.” In the evening the men come back and didn’t find anything. Renesse calls my wife with his kindest voice and pretends that he supported it for the judicial authorities to be allowed to let me go.

Towards evening I was free again and heard, when I arrived home, that our friend Toon Lampe was walking in the Plenkert (our street) just as police began surrounding the terrain. He then went to chaplain Horsmans (DB) who then warned my parents. These, in turn, asked lawyer Cremers to provide legal assistance to me if necessary. He then inquired at the Prosecutor for which reason a search was done in such a large format. No order had been given to officer Renesse.

Chaplain Horsmans had kept his word. That same evening, after darkness came in a few trusted men brought (without my knowledge) the weapons to another place. During the liberation I saw O.D. boys with guns walking without the bolts (ours?). One night two policemen came to bring me back the copper and said I better should put those barrels of soap elsewhere.

Shortly after this, a brother of the Jesuits came with a box lined with zinc into which we packed the chalices etc. We hided this box in the garage under the tiled floor, this time without witnesses. One gets clever from damage! I hung the mass gowns into a cupboard of the laundry and attached cards with the addresses of several South Limburg cloisters, as we usually did for our clients. My father and I hided the old books in a corridor around the safe of the former “Twentsche Bank” in Heerlen. (In 1939 Peter Schunck had bought a building of the Twentsche Bank in Heerlen, to build an arcade: the passage between the Emmaplein and the market.)

The story of these weapons had gone, with some exaggeration, like a wildfire by Valkenburg. In the street people whom I hardly knew came to me to congratulate me, one of them even said he would know a place for the weapons. However, I had learned a hard lesson. I knew now that one had to proceed prudently. You could say, I had got a crash course in resistance.

From this story we may conclude that meanwhile many people wanted to resist. But it also had other consequences. Not only that a Jewish person came from Amsterdam to Pierre Schunck to hide himself, see below, but also people who were already involved in hiding people for some time became aware of him. See further below.

Jan Langeveld

This house search also had the effect that people became aware of me, who were already busy with resistance activity at that time.

Just before the war, the organization of laundries had recommended me an accountant specializing in this area . Mr. Stoffels from Bussum. He had always kept distance from me. Since this search, his attitude suddenly became more open and he spoke of war and the enemy with me.

In 1941 the company A.Schunck in Heerlen got a problem with the section Confection on the production of mining clothing. Their license was endangered if no separate production line was created. I was invited to take this organization (in fact my profession). With Stoffels I consulted on the set-up of the administration and the way in which the management could be established. Stoffels knew a person in Amsterdam, who was at home in the textile business. He would ask him if he felt something like coming to Limburg.

“Jan Langeveld” 1992

A few days later he was back again and now with the message: Indeed, the young man, unmarried, is willing to come. He is a Jew and will come under false flag. Ideally, he would have a living within the company so he would not have to go outside. In 1942 the preparation is ready. the carpenter separated and shielded already a room behind the storage, where the diver could live. I did not know his real name and I did not want to know it. To me he was Jan Langeveld as featured in his ID certificate, which made a poor impression. It was treated with an eraser so that the surface was damaged. Something to attract attention at the first check.

After Jan Langeveld was already installed in our company and no one of the staff, who had come from the glass palace to the Geleenstraat with machines etc., had any wonder about the new manager (after all, a new company also has new people) both my diver and myself were somewhat relieved.

Since a vicar in Heerlen had problems with the clothing of his hiding fellow human beings, we got in contact with him. We were able to help him with his clothing problem and he promised to do something for me with the papers of our hiding man. This vicar was "Giel" Berix. The “diving work” of this vicar didn’t have contact with the national resistance yet. He and his people tried to help whereever it was necessary. Only 1943 the whole was organized on a higher level and taken to a countrywide network, with the participation of two vicars from Venlo and primarily an elementary school teacher Jan Hendrikx, alias Ambrosius. And so I became a member of the resistance so to speak from one occurrence to the next one, in the beginning as the man for the clothes of the hiding people and later as a subdistrict leader (of Valkenburg and surroundings).

If one suddenly would have asked me: come on, join in … then I maybe wouldn’t have had something to do with it, after down-to-earth consideration, and because of the dangers of a married man with children and a company with people who also would be in danger, to lose their jobs. Now I was driven into it. I accepted it and knew that it had to be that way.

At Schunck’s home

For Pierre Schunck, it was logical to do laundry for the German army. This was similar to the camouflage of the municipality official Freysen with his brown shirts and German-friendly chatter, while working at the distribution office of Valkenburg for the underground organisation L.O. During the war, our parents couldn’t always hide their opinion in front of the children already living. And so they took over this opinion, without any idea of the possible consequences.

The German soldiers who served in the occupied territories, were often less fit or older people who were not suitable for use on front. (At the end of the war that was quite different: so many soldiers had died that even boys and old men were sent into the battle.)

One day the two oldest children played outside. It was beautiful weather and the windows were open. An older soldier came to bring the laundry of his unit and saw the playing kids. He asks little Jan in an attempt to speak Dutch: “Well, kid, what’s your name?” “Jantje!” “And would you give me a hand?” Oh, no way! His older sister impossibly could allow this. “Give that Rotmof no hand!”

My mother, who heard all this behind the open window, thought to sink into the ground. Now everything would come out! But the soldier didn’t take offence at it and went on. He probably was just a nice man, who was thinking of his own children or perhaps grandchildren.

One day my father received the command to come (to Maastricht?) and to report to officer Suchandsuch of the german army. He had no idea what about it was. He washed for the army, but for that he never had to come to the barracks. Maybe it was about his candid little daughter? Then he maybe would get only a scolding, that he’d have to educate his children better. Or, which would be of course much worse, maybe someone had charged him? It was still about work for the laundry? Maybe it was better to go underground? No, because if it would turn out to be something harmless and he wouldn’t come, then he probably would wake up sleeping dogs. In addition, the employees would lose their jobs and thus, even his own family would sink into poverty.

He went full of doubts.

“Well, so you are Herr Schunck. Just tell me something. Your name sounds so German. Where is it actually from originally?”

“From Kettenis near Eupen. People speak German there.”

My father studied for a while in Aachen and was fluent in German. That and his descent from a German-speaking region, which had been annexed by Germany by then, made the officer decide:

“But then you are an ethnic German! Then I wonder why you didn’t already voluntarily report a long time ago for the eastern front!”

So that was it. That was a weight off my father’s heart. The relief made him eloquent. He declared that of course he would like to, but that he had a less heroic, but nevertheless not less important role to play. Finally he had to wash for the German army? And in addition, the income of a number of families depended on his laundry.

The mine strike

De overgang naar het grootschalige georganiseerde verzet waren de April-meistakingen, die in Zuid-Limburg vooral een mijnstaking was en dus ook zo wordt genoemd.

Op Wellerlooi, verzetsmonument lezen wij: In 1943 werd door ‘Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber’ generaal F. Christiansen aangekondigd dat 300.000 Nederlandse militairen alsnog in krijgsgevangenschap zouden worden afgevoerd. Als protest tegen deze maatregel brak spontaan overal in Nederland de April-Meistaking uit. Nog voordat de officiële bekendmaking in de avondbladen van donderdag 29 april 1943 verscheen, werd dit nieuws met hoge snelheid verspreid door heel Nederland. Diezelfde middag besloten verschillende personen van particuliere en overheidsbedrijven en instellingen in Twente te gaan staken. Ook in de Limburgse mijnstreek werd het in de loop van die middag onrustig. Lees meer …

Communiqué of the High Führer of the SS and the police of the provinces of Limburg and North Brabant on the death sentences related to the strike in the mines from April to May 1943.

On July 1, 1946, a mass grave containing seven bodies was discovered in Wellerlooi (municipality of Bergen) on the Wellse Heide (now the nature reserve Landgoed de Hamert). There an oak wood cross stands on a red brick wall, the resistance monument, as a permanent reminder of the seven resistance fighters Han Boogerd, Bob Bouman, Leendert Brouwer, Pieter Ruyters, Reinier Savelsberg, Meindert Tempelaars and Servaas Toussaint, shot in connection with the strike in 1943.

In the Dutch coal mining area this strike was called miner’s strike. The actual mining area stretched from Geleen to Kerkrade, but a not inconsiderable number of miners lived outside of it, for example in Valkenburg. In Maastricht, the strike was initiated by government employees. Later bank staff joined in. When the postal workers also wanted to go on strike, the members of the nazi party NSB present forced them to continue working with all sorts of threats. Long queues of people immediately formed in front of all the counters, wanting to buy one single 1-cent stamp. This way the post office was closed too. The factories also joined.

In the beginning there was a party atmosphere. People flocked to the pubs and didn’t suspect (or didn’t want to think about it) that the occupiers would of course not tolerate this and that there would be victims. These events made it clear that attempts to lure the Dutch with the status of an “Aryan brother nation” had failed.

The miners’ strike was part of the strikes of April-May 1943. The background was the return of Dutch soldiers to captivity, planned by the occupiers, to be put to work in the German war industry. They were the transition to a more massive resistance movement throughout the Netherlands, including the province of Limburg. The strikes were brutally suppressed, but the resistance organizations gained more new members (perhaps even because of this?). For the majority of Dutch Jews, however, it was already too late. :(

Zie ook het artikel: als de mijnwerkers staken tegen de Duitse bezetter. Met name de harde repressie, waarmee de bezetters deze staking te lijf gingen, opende velen de ogen. In dezelfde tijd namen ook de deportaties van joden steeds massalere vormen aan. Niemand geloofde meer in een humane bezetting, de verzetsorganisaties kregen toeloop.

Organised Resistance

in Limburg and Valkenburg - and the role of Pierre Schunck in it

The first organized resistance was based on demobilized soldiers. Like the clergy, they had the advantage of knowing each other well before the war. In Limburg this is the origine of the groups of Erkens, Dresen and Bongaerts. The Maastricht citizen Nic Erkens (DB) had contacts with resistance groups in Belgium. The Valkenburger Jan Joseph Rocks (DB) was also part of this group. Nic Erkens went into hiding in guesthouse Rocks, the later Park Hotel Rooding. They fell into German hands by infiltration through the Hannibalspiel of the German Abwehr (counterintelligence).

Some residents of Valkenburg and surroundings began already in 1941 with the help of first divers. A. C. van der Gronden (DB), a brother of G.J. van der Gronden (DB), who was detained on 13 January 1942, helped Jews and communists with accommodation in collaboration with rector G.A. Wolf (DB) from Sibbe. End of 1943 they joined the LO, subdistrict of Valkenburg. Carelessness and talkativeness of the diver A.S. Bron resulted on 17 February 1944 in the arrest of Wolf, Bron and the hidden person Th.M. van Santpoort. Wolf was released for lack of evidence after ten days and van Santpoort after several months. Bron was deported and survived the German camps.

During the farewell ceremony of his companion “Paul”, Theo Goossen (resistance name: Harry van Benthum) made a speech in which he described the activities of Paul, but also of the entire L.O. :

His acting mainly was aimed at assistance to people in trouble:

- To destitute families, whose husband and father had to flee, had gone into hiding, or was confined in jail or in one of the atrocious concentration camps.

- Organising accommodation and hiding places for refugees, for Jews, for crashed allied pilots, for Resistance people wanted by the police, etc.

Those people all needed nourishment, clothing, ration-books, identity cards, ration-coupons etc. - The realisation of this help demanded organisation, consulting together, intensive cooperation etc., and all this inconspicuously and in secret!

“Paul”’s own business interests again and again were interrupted by the distress of other people. This situation requires too: looking out, being carefull and acting inconspicuously. ALWAYS in the hope, to be able to evade the danger (though hidden, but always present). In this atmosphere we have to look at “Paul”’s more than 2 years lasting organised resistance activities.

In addition we have to take into consideration: several times he was in real peril of his life.

In his own words:

“I don’t understand. I cannot explain it. I was very lucky! But I prayed a lot!”. And he adds: “I didn’t do all this alone. And without the support by my wife lots of things would have gone totally wrong.”

The necessity to help the many people who went underground, Jews, crashed allied pilots, and former Dutch soldiers escaped from camps for prisoners of war, stimulated the need for more unity. Smaller opposition groups went to work in a larger context, namely in the L.O. (The national organization for help to people who went underground). They divided Limburg into 10 districts. Apart from this organization the “knokploeg” (task force, thug troop), called K.P. briefly, was set up. They got hold of ID papers and food ration cards, frequently under use of force. As of the end of 1944 the complete K.P. in Limburg was under the management of Jacques Crasborn from Heerlen.

After some time in Valkenburg a K.P. was created, too. It initially consisted of two men, the teachers Jo Lambriks (DB) and Jeng Meijs (DB), whose first had Jacques Crasborn as a pupil in his class some years before. Later Georges Corbey (DB) became the third member of the KP (fighting team) Valkenburg. The name evokes a violent thug gang, but most of the KP people were not combative, though of course sometimes they didn’t shrink from a forceful action, if necessary. The task of the KP was no other than to ensure the livelihood of people in hiding. (The L.O. provided the distribution). They gathered materials, illegal reading, ration stamps & cards and sometimes even German uniforms for use on the occasion of robberies. Most activities took place during the night.

Leader of the L.O. in Valkenburg was Pierre Schunck. Among others, Harie van Ogtrop (DB) and Gerrit van der Gronden (DB) were members. Of course there were more people, up to municipality officials, who cooperated now and then under a complete discretion. Thus it were the municipal officials Hein Cremers (DB) and especially Guus Laeven (DB), who ensured at the end of the war that the entire register of the registry office of Valkenburg “somehow” got lost, when the Germans had the idea to force all male inhabitants between 16 and 60 years old to dig trenches.

The organized resistance in Limburg started in the city of Venlo, in February 1943.

Here it is about the resistance organized at the provincial level. At the local level, individual acts of resistance were made since the beginning of the war, as listed above and others. This resistance achieved a continuously rising higher level of organisation, which finally resulted in the Limburg branch of the L.O.

A primary teacher there, Jan Hendricx (alias Ambrosius), became the leader of the L.O. in Limburg, supported by father Bleijs (alias Lodewijk) and chaplain Naus. The soul of the Limburg resistance was L. Moonen (alias Uncle Leo), the secretary of the diocese. By his help they established the necessary connections all over the diocese in short time so that Limburg had a well established resistance organization by the end of the year 1943.

The historian Christine Schunck, daughter of Pierre Schunck, writes: “Lou de Jong wanted to pull already late 1944 information from resistance people in Limburg, when the front was still quite close (think of the Battle of the Bulge). The leaders of the South Limburg resistance did not want to reveal any names and deeds. De Jong never returned after the war to get additional information, but simply wrote that the resistance in Limburg would have presented not too much. Luckily Dr. Cammaert has done a very thorough research with a light emphasis on Middle-Limburg, where his roots are.”

Because de Jong, not wrongly, is considered the most important authority in the field of the Second World War, many copied from him, so that also …

ID card

… in and around Valkenburg, nothing significant happened in this regard. The small private archives of Pierre Schunck (alias Paul Simons), one of the resistance fighters in Valkenburg surviving the war, prove the opposite. Not only his personal report with notes and pictures shows this, but also a number of genuine and forged ID cards, ration coupons, notes of underground people with secret messages (“from Z18 to R8”), illegally printed and stenciled matters, lists of official aid to war victims during the occupation, a file on Jewish victims.

Here are the testimonys on organized hiding aid in the region of Valkenburg during the years of German occupation, on the assistance to crashed allied pilots, the attack on the registry office, which made the deployment of men from this subdistrict in the German production process largely impossible; on the large scale manipulations of distribution records, which made it finally necessary to raid and plunder the distribution office in Valkenburg, so that falsifications not should come to light; on emptying a warehouse of radio equipment in Klimmen; on the hiding of precious liturgical vessels and chasubles from the Jesuit monastery in Valkenburg; on incidental stunts as the pillaging of a railway carriage full of eggs (decorated with a banner: “A gift of the Dutch people to the German army!”) and of a ton of butter from the dairy in Reymerstok.

This dairy worked for the Wehrmacht. With actions like this the German uniforms and the army vehicle mentioned below were very useful. The prey benefited particularly the hospital in Heerlen, where many divers were treated secretly.

Since a chaplain in Heerlen had problems with the clothing of his hiding fellow human beings, we got in contact with him. We were able to help him with his clothing problems and he promised to do something for me with the papers of our hiding man. This chaplain was Giel Berix. The “diving work” of this chaplain didn’t have contact with the national resistance yet. He and his people tried to help whereever it was necessary. Only 1943 the whole was organized on a higher level and taken to a countrywide network, with the participation of two chaplains from Venlo and primarily an elementary school teacher Ambrosius, alias Jan Hendrikx. And so I became a member of the resistance so to speak from one occurrence to the next one, in the beginning as the man for the clothes of the hiding people and later as a subdistrict leader (of Valkenburg and surroundings) .

If one suddenly would have asked me: come on, join in … then I maybe wouldn’t have had something to do with it, after down-to-earth consideration, and because of the dangers of a married man with children and a company with people who also would be in danger, to lose their jobs. Now I was driven into it. I accepted it and knew that it had to be that way.

Redistribution

Clothing for “divers”

I got in contact with chaplain Berix by the company. Because Berix tried to get clothing for (allied) pilots and divers here. He asked for overalls. I say: “Whom for?” “I can not say for whom. Just for poor people”, he said.

He asked for a rather large quantity, so I say: “If it is for the poor, I have to discuss that with Distex.” But he found that a bit dangerous.

It concerned his lack of working clothes for students who went underground at farms (1942). Giel offered, in return for my support in this matter, to provide identity papers and food bills for the Jewish hiding man in the company S.K.I.L. in “the mill” in Heerlen.

I had a Jew as a manager here, who was hiding under the name Langeveld, and he lived here as an Aryan.

We came to an agreement: the costs for the overalls with regard to consumption of material and paid-out wages would be paid by Berix from a fund of the diocese (fund for special needs).

It turned out that the required materials which Distex delivered in large quantities came from textiles from confiscated Jewish enterprises which had been given to Distex to redistribute. Distex didn’t write a bill and so the resistance movement didn’t have to pay for these deliveries. Since Mr Hogenstein of the Distex central store in Arnhem took the redistribution literally, which means from Jews to Jews, he emphasized that Jewish hiding people should have priority at the apportioning of clothes.

Then, Berix asked me, if I did ever something illegal. I said: "Yes, a bit. "

He probably had already the plan to organize the subdistrict of Valkenburg. I replied that I actually brought underground some paraments and golden chalices and books from the monastery of the German Jesuits in Valkenburg, who were driven out by the Reichsschule (school of the SS) , put together some car loads.

Berix found all that very interesting and nice and then he gave me the proposal to bring more people to Valkenburg, because he assumed that there were good opportunities to hide people in Valkenburg and surroundings. (I live in Valkenburg).

Founding of the L.O. district Z18 (Heerlen)

The time was ripe to join forces. An important impulse came from the hospital in Heerlen, where people were gathered for whom commitment to others, a common view of life and trust in each other were a matter of course. More details about the hospital below.Theo “Harry” Goossen (DB), as sub-district leader of Kerkrade one of the co-founders of the district of Heerlen, said during the funeral of “Paul” Schunck (DB):

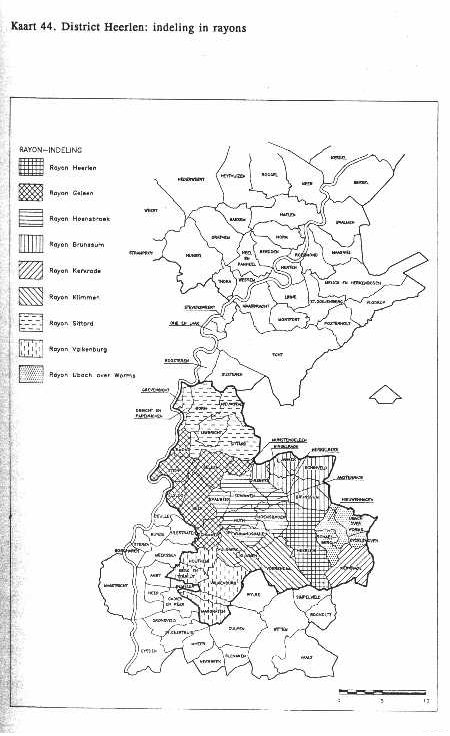

Curate Giel Berix (DB) from Heerlen, a friend of “Paul”’s and one of the founders of the L.O. in Heerlen, became after the retirement of Rector Prompers (DB) by some good reasons and according to his own wishes, the leader of the district Z18. The district of Heerlen was divided into 9 rayons.

The present Mr. “Paul” became the leader of the subdistrict Valkenburg. The activities of this group stretched away to and reached Gulpen and Maastricht. Also Klimmen and environs were incorporated with the subdistrict Valkenburg.

During several secret meetings and the necessary cooperation they got better acquainted with each other and some learned a little about each other’s familiar situations and even surnames.

“Paul”’s family name was Schunck, he lived in Valkenburg, where he had a laundry. There his wife Gerda was playing an important part too. At set times you could find “Paul” in Heerlen in a clothing factory at the corner Kruisstraat-Geleenstraat.

The resulting contact between the rayon of Valkenburg and the district of Heerlen was uncomplicated, because I was in Heerlen at work every day.

Furthermore we agreed that no hiding persons should be referred to the company but that the need of clothing should be transmitted for them by couriers.

More complicated need of clothing used to be regulated by the director of the municipal social welfare office, Mr Cornips (DB), with me. He was very competent for this due to his function. It was predominating about suits, clothes, coats etc. for families being hidden as a whole (primarily Jews) and suits and coats for prisoners of war (primarily Frenchmen) and pilots.

I had to deal personally with heavily solvable problems e. g. with a very thick Franciscan monk, friar Beatus (DB) and also with a very tall one, friar Amond. There our work had to to be made to measure.

The son of this Constant Cornips was Jan Cornips, the secretary of district leader Berix of the Heerlen resistance.

Read more about the great networker friar Beatus van Beckhoven on the Dutch Wikipedia

The “diver’s inn” in the Caves of Meerssenerbroek

From Pierre Schunck's interview with the Auschwitz Committee:

Since the thirties my father exploited a lime quarry (Near the Meersenerbroek between Geulhem and Meerssen, Open Street Map.) The lime was crushed to small pieces and sold to the farmers as a fertilizer. The director of this company was Heinrich S., a German mining engineer, who lived in Holland. However, his main activity concentrated on a quarry with natural stone trade in Kunrade, in the possession of my father as well.

Until May 1940, this brother-in-law had always given the impression on us to stand extremely hostilely opposite the Hitler regime. We were therefore very astonished to hear that he had been appointed "ortsgruppenführer" (local group leader) by the German nazi party in Heerlen and that he had got a controlling function in the common mines in Limburg as a secretary of the German pit administrator.

In 1942 I heard from chaplain Berix (DB) that a chaplain in Meerssen (DB) was hidung two boys who were looked for by the Germans in the cave belonging to my father. Information confirmed this and I was allowed to pay a visit to these boys. The chaplain swore me, that he knew everybody of the staff of the lime works, and that each one of them was completely reliable. But he didn’t know that the boss was a German party functionary.

In fact, that was the foundation of the rayon (subdistrict) of Valkenburg and they were my first divers. This was done in consultation with chaplain Geelen. (DB)

Here Pierre Schunck leaves the Dutch soldiers out of consideration, that he sent on their way home in the first days of the occupation after they had been waiting for a while in Valkenburg on the tourist season. See above.

Luck played in our favor. My father was in conversation with Heinrich S. about the top-level position of the enterprise because of his workload on the pit and in the party. I knew a student graduated recently in Leuven, he now was an agricultural engineer. He was a brother of one of our priests in Valkenburg, and he was called graduate engineer Horsmans (DB). I asked him whether he would feel like, temporarily, taking on the work of my brother-in-law in the Meerssenerbroek (as long as the war would last). My father and Mr Horsmans reached an agreement.

Berix and I had come onto an idea for these caves in the meantime.

First the guys of chaplain Geelen were in there. But you can not stay longer than three months under the earth, then you have to go again into the fresh air. So in my opinion it would the best idea, to install a diver’s inn there. We accommodated the guys of chaplain Geelen in Schin op Geul at a farm (we took them over completely).

So the cave became a diver’s inn, and if I happened to have no place free and I got but new entries, then I said: “Just let them come”, then I put them in the cave, and they were sure for a while.

Building up the “diver’s inn”

On the basis of a map, Pierre Schunck shows an American soldier the tunnel system in the Dölkesberg.

Photo: Dwight W. Miller

Source: https://nimh-beeldbank.defensie.nl/beeldbank/

Our young organization was absolutely dependent on its own efforts to offer places to hide to people pursued by the enemy. We were not yet associated with a nationwide organization (the L.O.) and it was even still unknown to us (until 1943). Given the tense situation at the universities and the raids after Jews in the North, Berix (DB) feared that we suddenly would have to manage large groups of people. Such a cave would fit exactly as a temporary refugee accommodation. Enquiry among the staff in Meerssen, about the behaviour of S., showed in response: "We only see S. visiting quickly the office, the lime kiln and the open pit quarry. He never enters the underground caves and he also doesn’t know his way around there."

Chaplain Berix found it rather positive that a German party functionary who didn’t know his way around in the cave was the director. The German authorities would never become suspicious against this place.

In the winter of ’44–’45, Pierre Schunck and a comrade play for a film team of the American army how a person is brought into hiding to the Diver’s Inn

In the middle the remains of an old lime kiln, to the left and right of it entrances to the mine. In the area in front of it are still the foundations of the lime works after which this cavern has been named: “Behind the Lime Works”.

There were two caves, completely independent of each other. Coming from Valkenburg, the first cave was behind the lime kiln. It was built in the 20th century, very regularly like a chessboard, in the way of a modern “block breaker quarry”. The only entrance was accessible and visible to everyone. The second cave was below the fruit meadow of my father’s and was not used for the limestone extraction anymore. Its entrance was (and is) almost completely concealed by bushes, only accessible by a steep slope. In front of the entrance was the cottage of Sjir Jansen (DB), a very simple man but a great guy, through and through reliable. In the past this cave was used by the Montfortan fathers from Meerssen. On days off their pupils came to paint wall pictures and they also made a fun to imitate a chapel in the way like they are still found from the French time in the caves of Valkenburg and Geulhem.

This chapel was built by theology students, especially inspired by the nearby underground clandestine church in Geulhem, built during the French occupation by Napoleon.

Photo: Dwight W. Miller

Source: https://nimh-beeldbank.defensie.nl/beeldbank/

Film

We choosed this cave to be our “diver’s inn”.

It wasn’t our intention to set up a durable place of residence for hiding people here. It nevertheless still had to get a bit more comfortable. Firstly, it was rather damp. The temperature is there only durably 10° to 12° degrees Celsius all the year round, just a little too cool to feel well. Berix knew a solution for it. A long electric cable was put to the hiding-place by employees of the coalmine Oranje-Nassau. By arrangement of another Berix acquaintance, a technician of the electricity supplier PLEM installed a safe electric heating, light and an electric cooker. I found electric cookers, light elements and electric heaters in the Jesuit cloister as well as dishes and kitchen utensils. The cable was attached directly to the net without an electricity meter in the control cubicle of the lime kiln.

Furthermore there had to be a escape opportunity, for if the entrance would be blocked by the enemy. It was created by scraping out a doline, a loam tube which led into the Berger Heide (Berg Heath) and which should remain disguised well by the brushwood.

We also had to supply warm meals for the hiding people. Later, in the L.O. time, food coupons were no problem. But at the planning time, we couldn’t yet fall back upon them. Of the food which actually was intended for the children’s eating house in the laundry, my wife put the required part aside and cooked the meal for the cave with that. On weekdays the van of the lime works fetched this food with us and at the weekends I had to take care of it with the bicycle.

Jan has been in there. (Jan Cornips, the secretary of our district leader in Heerlen.)

The district leaders lived there for a while, and people from other districts. I provided them well with good food, even wine and playing cards and my radio stood ready. There was electric light, that was all right.

Berix (DB) and I organized the needed cable at the muncipal services.

In the interview with the Auschwitz Committee, he speaks of a cable from the mine Oranje-Nassau. Possibly, they did not have enough with one cable, because the distance to the switch cabinet was too long.

We organized the mattresses with the nuns of the hospital. That was easy! One evening my wife (DB) got an order for blankets and so I went looking for mattresses as well. We went to Heerlen, where we were able to take some blankets at the company (Fa. A.Schunck). But they had no mattresses. I talked about it with Berix, and asked him, “Couldn’t we get a licence for that in the hospital?”. Then Berix said: “I was there for a visit some days ago, and if you look around there, there is a hallway and there is one mattress next to the other.”

I went there immediately with Berix. The housekeeping nun asked: “What do you want?” “Well, mattresses” we said. She said: “Just take them if the chaplain says it is all right. There they are!”

And we started to carry them away.

But at about ten o’clock the sisters came back and wanted to go to bed. They used to air the mattresses on the floor and we had taken them now!

But in any case, the boys in the cavern had mattresses to the sleep on now.

There, we had about 20 flatbeds. We originally designed the whole thing for pilots because the pilots were a problem for us. They had to be dispersed, and someone came up with the idea: “Why don’t we hide them in a cave?” We set up this thing then. We had the famous family F[****] in there with 9 married men from the same parents. They came from Poland, and they refused en-bloc to join the German army. I had seven of them myself. I made them dig out a cave that was not yet known. With emergency exits, electrical lighting, radio, bath, a sink, a paraffin stove for cooking etc.

This was the pilot’s cave. It is used only by the workers who set it up. We measured the cave to find out the most convenient point for an exit to the forest. We shocked there an old woman who was searching for acorns. Suddenly someone came out off a hole upwards! (We were trying out secret exits).

This was a so-called organ pipe or doline, a Karst phenomenon in the shape of a funnel.

Mouth of the cavern Bronsdalgroeve 2019